Inside the temporary housing provided to Mudiaga, Lamin and Seykou through a resettlement agency called the System for the Protection of Asylum Seekers and Refugees (SPRAR).

Located on the coast of Italy’s Strait of Messina, Villa San Giovanni is a small, unassuming town in the southernmost Italian province of Reggio Calabria.

Once known for its mulberry crop and silkworm breeding, the area is now known for the colorful festival of Saints Cosmas and Damian. It has also become a temporary home for a group of three refugees fleeing from Libya.

Mudiaga, 29, Seykou, 20, and Lamin, 18, made the dangerous journey across the Mediterranean Sea to Italy after mounting chaos and violence in Libya forced them to flee.

The three now live in a four-story concrete building in Villa San Giovanni that was provided by an Italian resettlement organization called System for the Protection of Asylum Seekers and Refugees. The apartment is sparsely furnished with secondhand mattresses, suitcases and neatly stacked piles of personal possessions — a New York Yankees hat, a 2003 Bob Marley calendar, a hardcover Bible and a pair of bright soccer cleats.

Mudiaga spends his nights in his room reading the Bible and an English language dictionary.

Seykou holds a pair of yellow soccer cleats he wears to soccer games hosted by refugee agencies in Calabria.

A New York Yankees hat sits on a pile of books in a shared living space in the house.

Seykou watches the Argentina v. Paraguay game on the television set in their home.

When we visit them, a rerun of the 2015 Copa America soccer game between Argentina and Paraguay is playing on an old television set in the kitchen corner. Some of the men staying in the apartment are hanging clothes for laundry day.

Italian soccer jerseys, worn undershirts and patterned bedsheets hang from colorful plastic clothespins on the west side of the apartment. A young man checks his Facebook on the narrow balcony on the other side, with a stunning view of the sea wrapping around Sicily as his backdrop.

We sit around a table in the kitchen with a blue-checkered tablecloth like those you’d see in quaint, street-side Italian cafes. The three men, eager to share their stories, offer us cups of soda and biscuits before we begin the interview.

They asked us to only use their first names to hide their identity, concerned that sharing too much information may jeopardize their pending asylum cases.

They have all had incredible journeys.

Seykou, ambitious and well-spoken, left his home in Gambia and traveled through Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger before arriving in Libya in 2011. Mudiaga made a similar journey to Libya from Nigeria in 2007 and Lamin from Gambia in 2012.

Before the war started, many people from neighboring African countries moved to Libya in search of work. They found jobs as mechanics, bricklayers, plumbers and construction workers — jobs that middle and upper-class Libyans were gladly handing to undocumented laborers.

The 2011 uprising, overthrow and subsequent murder of Muammar Gaddafi initially spurred promises of democracy and further economic opportunity for the country.

Those promises were quickly replaced with a brutal civil war and political chaos.

Mudiaga moved to Libya in February 2007. He quickly found work as a welder and fabricator at a small company in the capital of Tripoli. He said he found great satisfaction in his work and was able to set aside savings, which he was not able to do at home in Nigeria.

But after the collapse of the government, the company where Mudiaga worked shut down.

“When the war started, everything just finished,” Mudiaga said. “It is a big war with machine guns and bullets flying.”

Lamin was in Libya for 16 months, and like Mudiaga, found steady employment, which allowed him to send money to his family in Gambia.

“I decided to leave Gambia to have something for my family,” Lamin said. “First, I was in Senegal working, but there, money is not powerful. So that’s why I went to Libya because the money is like Europe.”

He said when he first arrived there was a break in fighting, but about a year into his stay, the conflicts between the divided factions started up again, making it unsafe for him to walk out of his front door.

Seykou moved to Libya in 2011 to join his family who had started working in the country. In the beginning, life in Libya was serene, he said. He was grateful to be close to family.

But one day on his way to work, Seykou was kidnapped and put in prison where he would spend the next three months.

“I decided to come [to Italy] to save my life,” he said. “Before, there was no war there. Everybody was equal in Libya. By the time war started, black people had no chance … So from there, I decided to sacrifice my life...and God help me, I survived.”

As the fighting worsened, all three men made the same choice that thousands of others in search of a better life make each year — to leave Libya and risk a dangerous journey across the Mediterranean. The political climate in Libya provided an ideal opportunity for smugglers to freely move individuals like Mudiaga, Seykou and Lamin into Italy.

Two of the men walk up the stairs to a second living space for asylum seekers.

Though the three men made their journeys at different times, the common thread of hardship ran throughout their trips across the Mediterranean.

Mudiaga said he had brought biscuits and bottles of water to the port, but the smugglers ordered him to leave everything behind. For three days, he did not have a drop of water.

Disoriented and dehydrated, he was deeply relieved when the Italian boat rescued him, bringing him to the tiny island of Lampedusa. After being held there for nine days, he was moved to Torino for two weeks and then finally to his current temporary home of San Giovanni.

Like Mudiaga, Seykou also didn’t eat or drink for three days on a small fishing boat crowded with over 300 people. On the third day, he fell unconscious.

“I was [on the boat] for three days. I was flat. Our water was finished,” he said. “So by the time the Italy people came and rescued us, I didn’t know how I ended up on the boat ... I thank God because I don't die in the sea. Thank God nobody died in the sea.”

The boats transporting Mudiaga and Seykou made it safely to shore, but that was not the case for the boat carrying Lamin.

“Our boat — we were 110 people in the boat,” he said. “We were on the boat almost seven hours. Our boat had problem, and many people died.”

“Fifty-five people died in our boat. And 55 people survived … It's the God, you know... it was their time. The time that God opened their books and said this day, you will die.”

According to the International Organization for Migration, more than 3,700 refugees drowned in the Mediterranean in 2015 attempting to reach Europe.

The three men pose for a portrait inside their temporary home in San Giovanni.

Though the three men made it safely to Italy, their journey is not yet complete.

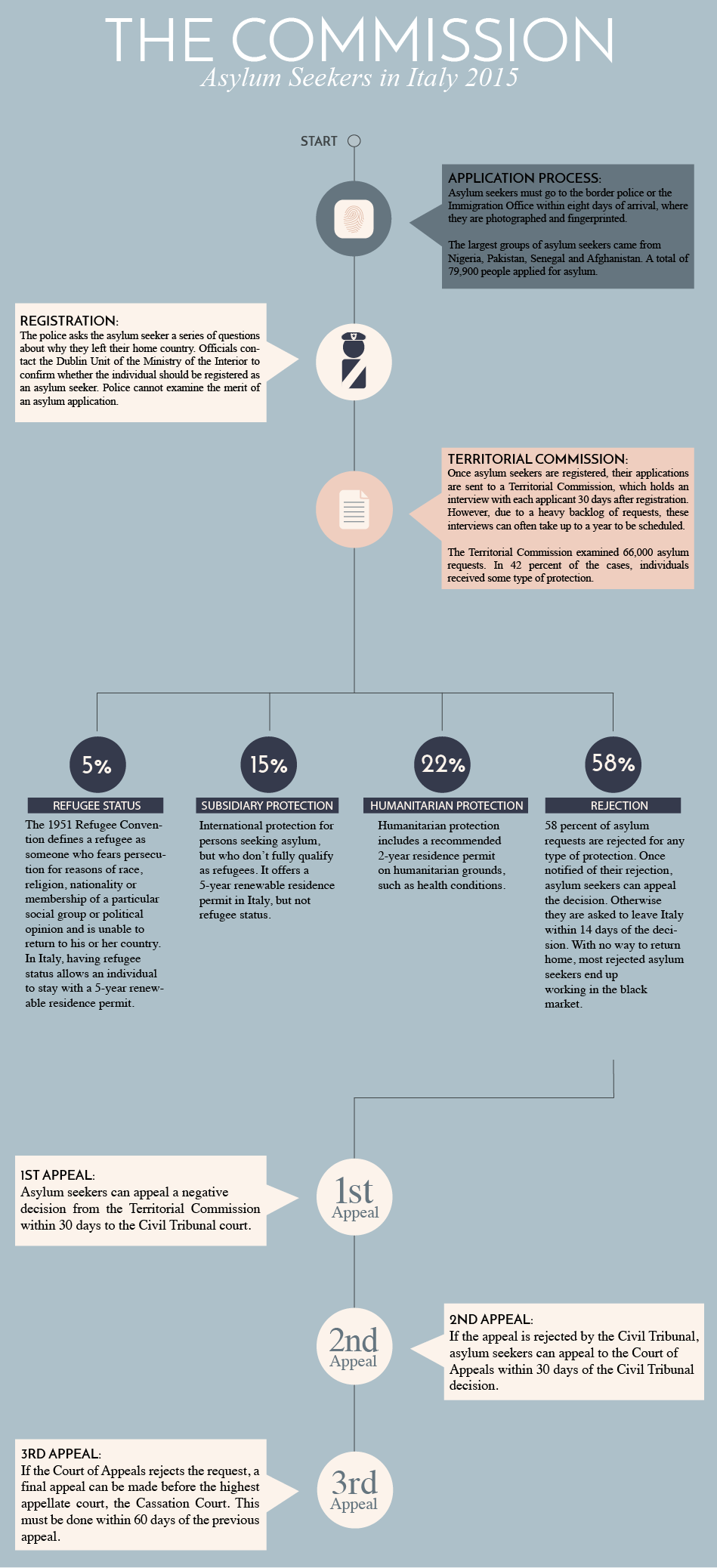

In Europe, there is a common set of rules that fall under the Dublin Regulation, a law that decides which European Union member state is responsible for examining applications for asylum seekers looking for international protection. The main goal of this EU law is to prevent people from applying for asylum to multiple member states.

When Mudiaga, Seykou and Lamin arrived in Italy, they had eight days to present themselves to either the border police or the provincial police station, where fingerprinting and photographing take place. The three men were fingerprinted and registered in Italy.

Now, according to the Dublin Regulation, they must process their request with a local Italian Territorial Commissions or Sub-commissions for International Protection. These commissions, which fall under the Department of Civil Liberties and Immigration of the Italian Ministry of Interior, are wholly responsible for granting individual decisions on asylum cases in Italy.

According the the Council for Refugees, in 2015, 55.2 percent of asylum seekers were denied any type of protection. While they can appeal the decision, asylum seekers are often rejected a second time and given 14 days to return to their home country. Many remain in the country undocumented.

“If you don’t have documents, there is nothing you can do,” Mudiaga said. “Nothing. It’s a big problem,”

Without paperwork, refugees in Italy cannot apply for employment or find long-term housing, and they risk deportation if caught by local police.

“The future is hard,” Mudiaga said. “ Not for everybody. But right now, it is not good for us.”

Under the current asylum procedures, life for those entering Europe is uncertain. Those applying for asylum need to prove persecution in their home country from war. who do gain asylum through the Italian system are left to find jobs and housing in a country with a low employment rate and steep discrimination against refugees.

Those who do not obtain documents either have to return to their home country or live undocumented in Europe, making it nearly impossible to find jobs and assistance from agencies.

Last June, Seykou found out that he was denied documents from the Commission.

“For me, from the Commission, I have negative,” he said. “I don't have documents. It is very difficult for me because now I face difficult things. It was difficult in Libya, but thank God I escaped from there. But in Europe, if you don't have documents, still, now your life isn't back. So you cannot survive. I cannot stay here. I have to focus and do something or go to another country to get documents.”

In September, he left San Giovanni to try and find work in other parts of the country. His housemates have not heard from him since.

After two years of waiting for a Commission date, Mudiaga had his commission hearing in July.

While he was waiting to hear about the decision, he said, “For now, I don't know about my documents or if they will give to me. I don't know for now. It depends on your story, whether it is good enough. Why did you leave your country… that is the biggest question for you.”

--

We checked back with him at the end of 2015, and he said that he had been approved for two years of asylum but was still struggling to find a job.

“The truth is, in Italy, it is hard to look for work, especially with black skin,” he said. “Luckily, I can stay in the [SPRAR] project for three months until I have to leave.”

Lamin still waits for a Commission date. He hopes to stay in Italy, pursue his education and continue playing soccer with a group of young refugees he has met through the program.

“You know, life is full of changes. I'm 18 years old. I want my future to be good. But right now, I cannot tell you I want to be this or that,” Lamin said. “Right now, I want to go back to school to educate, because I'm 18 years old… In Gambia, I wanted to be a journalist just like you.”