The image of overcrowded boats with hundreds of refugees arriving on the coasts of Southern Europe is one that we have grown accustomed to, especially during the last couple of years as the Mediterranean refugee crisis has moved to the center of the media and political spotlights.

Though the number of refugees crossing the Mediterranean Sea has dramatically risen since 2014, the situation is not new.

In 1998, a boat with over 200 Kurdish refugees, who had sailed from Istanbul, arrived on the coast of Riace, a small southern Italian town. The landing, it turns out, would change the future of the town.

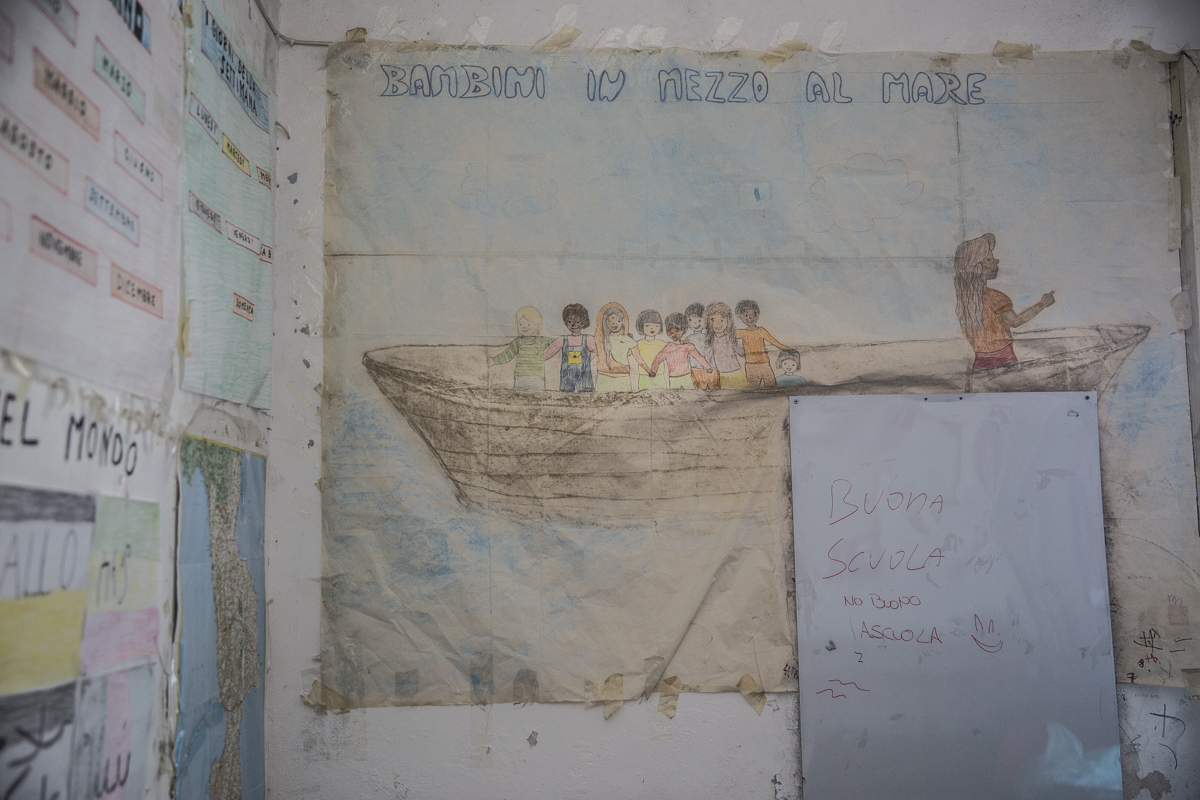

A drawing by children at a local school depicts refugees on a boat in the ocean. It read, “children in the middle of the ocean.”

After the arrival, then teacher Domenico Lucano and some of his friends founded Città Futura (“City of the Future”), an organization dedicated to helping refugees settle and adapt to life in Italy. They envisioned a city that would welcome refugees.

But the initiative also sought to address a local issue. For years now, Riace has been a dying town as the young population moves north. Attracting newcomers had the potential to revitalize Riace.

That is still the case today. In 2015, the unemployment rate for people under 25 in the region of Calabria was almost 60 percent — the seventh highest in the European Union. Corruption and organized crime in the region have also encouraged young people to leave.

Lucano, who has been the mayor of Riace since 2004, and his friends decided that welcoming refugees and training them in local trades would be cheaper than keeping them in refugee detention centers.

Though only one of the Kurdish refugees who initially arrived is still in Riace today, many more have come since. The town’s population has tripled since the late 1990s. It now has 2,800 residents — 400 are refugees from over 20 nations.

Signs at a local school show how to write ‘hello’ in multiple languages

Young refugee children carry water back home

An old woman from Riace looks at two African refugees. One of the men had arrived to the town only a few days before. The arrival of refugees has brought a wave of young people and children to the town.

A ‘bonus,’ the local pretend currency, depicts Francesco Basaglia, one of Italy’s most prominent psychiatrist, who was at the forefront of mental health reform.

The influx of refugees prevented the closure of some local schools, that wouldn’t have had students otherwise.

Furthermore, the model that Città Futura developed has boosted the local economy on a small scale. Newly arrived refugees are trained to work with locals on artisanal trades like weaving or glass blowing. They receive a salary and the products they create are sold mostly to tourists.

To support the initiative, the Italian government provides the town of Riace with 30 euros per refugee, per day. But because things in Italy move slowly, sometimes the money doesn’t arrive on time.

To solve the problem, Lucano designed a system of pretend currency known as ‘bonus.’ The game-like bills allow inhabitants to buy and sell goods until the real money arrives. They depict iconic figures like Che Guevara, Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.

Raffaele Niciforo, a man from Riace, sells his fruits and vegetables at a street stand. Niciforo has seen the change in the city.

Tahira, a refugee from Afghanistan, sells her embroidery products at a local shop sponsored by Città Futura.

While the model is successful in many ways, something feels odd and performative when you walk across town. Perhaps it’s the media fatigue that comes from being a model town where tourists and outsiders are constantly snapping photos. They are amazed at seeing Italians and refugees interact.

After all, Riace appears to the world as an exemplary model of integration in a country — and a continent — that is anxiously looking for answers on how to respond to the refugee crisis.

A mural in town shows clouds floating with the names of the home countries of refugees that have arrived to Riace. The mural reads, “where are the clouds going?” Riace continues to try to answer that question.